Early Bodybuilding History - Making Muscles Before the Weider Principles

Our Sport of Bodybuilding has a Long and Exciting History

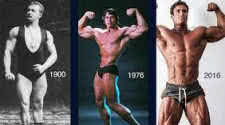

The metallic clink of steel against steel, the smell of sweat, the grimaces of effort, the grunts of exertion: Down through history these have

always been the unmistakable signs of bodybuilders at work. Modern musclemen often lose sight of the long chain of experience and tradition

that links them with the past. They often do not realize that it is no accident today's men of muscle have a unique look. A massive body like

Arnold Schwarzenegger's would have been inconceivable even 30 years ago.

A champion is always a champion, and the work of building muscles is just as hard now as it was then, but our techniques have undergone a

transformation as revolutionary as the bodies they build. A look back at the early days of bodybuilding will help clarify the origins of our

sport and the evolution of the techniques that brought us where we are today.

Not until the late 1800's did serious bodybuilders have the knowledge and the technology to start working their muscles in an organized way. The

turn of the century saw many revolutionary changes, and one of the most amazing was the rebirth of interest in physical culture and health.

Suddenly, everyone wanted to exercise and grow healthy, and standing by ready to help was a host of strongmen willing to guide the uninitiated

through the often mystifying iron jungle.

Mighty musclemen of that generation had two options for making a living. They could either go on the vaudeville stage as performing strongmen,

or they could become teachers. Most chose to do both. Perhaps the greatest of these old-time iron men was Eugene Sandow, for when he burst upon

the American scene in 1893, he completely changed the way the public viewed strength, health and muscles.

After a successful tour of American cities, Sandow knew that he could put the fame he had gained to profitable use. When he returned home to

Europe, he began a mail-order course that became the model for the many muscle-by-mail magnates who came after. Fortunately, Sandow had a winning

combination: high name recognition as a strongman, good easy-to-follow exercises, and instructions that called for relatively inexpensive

equipment. No wonder the German muscleman soon had a leading edge over all competitors - it was an edge he gave up only by dying, in 1925.

One of Sandow's first attempts at exercise equipment was his leg machine. This device, a complicated series of pipes, cords and stirrups, was

supposed to build up the thigh muscles. The inventor was shown demonstrating the device in his first book, published in 1894. Never mind that

the contraption looked like it would be more at home in a medieval torture chamber than a gymnasium - it was the best and cheapest machine of

its kind. Despite its gawky appearance, the directions for its construction show just how simple it really was: Two upright poles were set about

5 feet apart; attached to these were rubber cables. The athlete strapped the cables around his knees and pulled on the strands with his legs,

working the muscles of the inner thigh.

We don't know just how many burgeoning athletes chose to construct these devices, but the number must have been great. Even Joe Weider

confessed to having built the leg machine in his formative years. It was virtually the only device in existence then that performed the task.

The leg machine might have been Sandow's earliest attempt at bodybuilding equipment, but it certainly was not the only one. Another device popular

with athletes at the turn of the century was Sandow's patented Spring-Grip Dumbbell. This odd gadget consisted of a simple 5-pound dumbbell that

had been sawed in two laterally. Between the two halves was a series of heavy-duty springs, which the user compressed while raising and lowering

the dumbbell, so that the device built not only arm strength but grip strength as well. One of Sandow's pet theories was that an athlete must

focus mentally on the muscles he worked while he was using them. The Spring-Grip Dumbbell was specifically designed to aid in this intense mental

concentration. In the '20s, Sandow added another feature to his invention - a bell. When the two sides were compressed all the way, a little bell

would ring, indicating a successful lift. Difficult though it was to get people interested in his dumbbells, Sandow found that other items

almost sold themselves. One was a creation that he dubbed Sandow's Own Combined Developer. The strongman touted his invention as a combination

rubber exerciser, chest expander, light dumbbells and weightlifting apparatus. In reality, the design was not nearly as revolutionary as Sandow's

advertising might lead one to believe, for he had merely added light dumbbells to the handles. Nevertheless, these developers became very popular,

and they helped convey Sandow's name before the public as an unrivaled expert in the realm of physical culture. By the time the 20th century

arrived, there seemed to be a Sandow's Developer in just about every household in the Western world. Surprisingly, the apparatus has even crept

into modern parlance, for to this day in France the word for any rubber cable has remained with Sandow.

No matter how successful the devices Sandow and others marketed, one important point must be kept in mind: All the wall developers, light

dumbbells and thigh machines in the world simply will not build the kind of bodies that serious athletes want. As every bodybuilder knows, a

really impressive physique can be built only with heavy weights. So if athletes wanted to go beyond the usual run of popular exercises, they

had to consult an instructor who was familiar with this area of development.

Perhaps one of the finest of the pioneer coaches was Professor Anthony Barker. Born in 1868, Barker was destined to become one of the most

familiar names in the history of early bodybuilding. He first achieved renown as one of the mail-order fitness instructors who operated at the

turn of the century. It was hard to open a magazine and not see Barker's stern features staring at you, offering health, strength and physical

perfection if you would take up physical culture. Apparently, it was an offer few could resist, for Barker's practice grew rapidly. The professor's

success was fortunately based on solid principles and common sense - a winning combination in any field.

Barker's expertise is confirmed by his lengthy professional career, for he has the distinction of being the longest-lived of all the old-timers.

He was still active in 1961, dispensing information and advice. When he died in 1974, he had reached 106 years.

But Barker's legacy to the sport of bodybuilding goes beyond simple longevity, for he set down in clear and simple prose some of the earliest

and soundest advice on weight training. In 1902 he published a work called Physical Culture Simplified, and in it he explained his understandable

and no-nonsense approach to muscle building.

Two years after Barker published his book, one of his former pupils came out with his own work on the subject of physical culture. Al Treloar, a

noted vaudeville strongman and a talented coach, produced a volume titled Treloars Science of Muscular Development. In it he adapted some of

Barker's techniques and added a few ideas of his own. Treloar even included many exercises for women. Using his own wife, Edna Tempest, as a model,

the author took pains to illustrate the work appropriate for ladies. The author's female readers were advised to work out regularly with light

dumbbells, wall exercisers and sensible calisthenics.

The exercises in Science of Muscular Development largely reflected the conventional wisdom of the day. Treloar advised using a wall developer and

the usual 5-pound dumbbells. This work obviously was not aimed at the serious muscle builder, but rather the average, out-of-shape man or woman.

Light weights and high repetitions were what the author recommended. But what if you found that you could do more than the usual 10 repetitions

suggested? Increase the number by 10 or 15. In a masterpiece of understatement, Treloar counsels his weary pupils, "When an exercise can be done

easily 60 to 75 times, some more severe form should be used for the same muscles, either by using a heavier weight or assuming a more difficult

position." When enterprising athletes had to repeat a motion up to 75 times, it is a wonder that more old-time bodybuilders didn't perish from

sheer boredom.

While Treloar and his students were toiling away so laboriously, others were headed in a more reasonable direction. George Hackenschmidt,

nicknamed "The Russian Lion" by his admirers, was one of the finest of the old-time bodybuilders. He possessed one of the most muscular bodies of

his generation, and fortunately he was not shy about telling the rest of the world how he built his massive physique. In 1908 he published a work

called The Way To Live, and in it he gave detailed instructions in weight training. Here the author first revealed his use of an exercise ironically

called the hack squat. This was not named after the great athlete as some have supposed, but rather from Hacken, the German word for heel. This is

how Hackenschmidt described its operation: "Hold a barbell of from 10 to 20 lbs. weight behind the back with arms crossed, heels together, toes

pointed outwards. Now make a deep knee bend, rising on your toes, parting your knees, until almost squatting on your heels. Rise again to first

position."

Due largely to this lift, Hackenschmidt was able to build his own massive thighs. Thanks to such improved techniques, bodybuilders were now able

to perfect parts of their musculature that were previously difficult to build. After all, the hack squat is a great deal more efficient than

Sandow's awkward leg machine from only a few years before. With Hackenschmidt's knowledge and experience as a guide, others were undoubtedly

inspired to make progress of their own.

Even as the muscular Russian Lion was building his physique, others were also busy. The enterprising young weightlifting coach Alan Calvert

advocated a measured and reasonable approach to the subject of weights, strength and general fitness. Many of his early ideas were presented in

The Truth About Weight Lifting, published in 1911. This book was intended as an expose of the common tricks and sleight of hand used by the vaudeville

strongmen, but it was apparent to anyone reading the work that it was much more than that. It was, in fact, an early manifesto on the science of

weight-lifting and bodybuilding. Plainly not a work for the amateur or dilettante, this was one of the first comprehensive looks at modern

bodybuilding.

But Calvert's contributions to body-building went far beyond simple theoretical writings, for he also began manufacturing the very type of weights

he proposed lifting. The story goes that he admired the heavy barbells used by Sandow, but when he found it nearly impossible to acquire some like

them, he solved the problem by manufacturing his own. These proved to be so successful that he was soon supplying others with similar body-building

tools, and from that humble beginning was born the Milo Bar Bell Company, one of the largest and most famous of the old-time equipment sup-pliers.

Many an athlete from the early days of bodybuilding lifted Milo weights in order to form a better physique.

Typically, when he could not find an adequate forum for his ads and advice, Calvert simply began his own. Strength began publication as a magazine

in 1914. Originally it was distributed free to all who wanted it, but by 1917 Calvert found that he was giving away 45,000 copies a year, and he

decided that he had better sell the journal.

For many years, Strength was the leading publication in the field of weights and bodybuilding. It is hard to imagine an old-time athlete who did

not read it. Many of them were featured prominently within its pages. Otto Arco, Siegmund Klein, Clevio Massimo, Charles MacMahon and many others

first made a name for them-selves through the pages of this important journal.

One of those who had seemingly snatched the mantle of bodybuilding guru from Calvert's shoulders was Mark Berry. He began publication of an important

magazine in the mid 1930s called The Strong Man. Like Strength, Berry's journal attempted to keep its readers abreast of the latest muscle-building

techniques. He reported on strength stars, both current and up-and-coming; he handed out training advice; and he passed on important tips on lifting

and equipment from his readers. In all, it was an important addition to the athlete's library.

Perhaps one of Berry's greatest strengths was his willingness to try new things. He was continually reporting innovative techniques either in The

Strong Man or in his books. In this way he was able to disseminate many revolutionary bodybuilding procedures that might otherwise have gone

unnoticed. It must be admitted, however, that some of these muscle-building methods never really caught on. For instance, take this 1930 description

of a New Two-Hand Curl.

"Standing erect, bar bell hanging at arms' length in front of the thighs, you are to curl the weight, but not while holding the elbows in a fixed

position at the sides. Instead, the bell is to be drawn straight up along the front of the body as high as you can bring it by pulling the elbows up

in back, then, having reached the maximum height of pull in that direction, move the entire arms forward till the bell is in correct finishing

position for the curl. Lower by reversing the movement."

While Berry and Calvert were at-tempting to sell their own particular brands of physical culture, George Jowett, a bright Canadian mail-order muscle

peddler, was pursuing the perfect body. Rather than relying on fads and gimmicks, Jowett saw that muscles could be built only by hard work and

serious lifting. His mail course was not only helpful and informative, but also inspirational and well written. The Canadian strongman and master

teacher's influence would spread far and wide.

More than anyone else of his generation, Jowett gave bodybuilding a form and organization that it had previously lacked. In addition to supervising

his mail-order business, Jowett was also the editor of several magazines, most notably Strength. Later he began his own publication, Bodybuilder.

These positions soon made him a force to be reckoned with, and he added to his prestige by becoming one of the founders of The American Weight

Lifting Association, the forerunner of the present AAU.

Jowett's skill as a lifter, coach and writer helped him gather many important students. The late Bob Hoffman was one of Jowett's early disciples,

and because of his instructor's assistance, Hoffman was encouraged to start his own magazine. The greatest of Jowett's pupils, however, was Joe

Weider. He took the older man's teachings to heart, learning more from him than from any other old-timers who came before.

Despite being eclipsed by Weider, Jowett remained proud of his former pupil, declaring often that his protege would modernize bodybuilding. By the

early 1940's this prophecy had obviously come true. Young Joe Weider had clearly taken the sport of bodybuilding farther than Jowett had in his entire

liftetime. When a colleague reminded the older muscleman of this situation, Jowett replied in a typically gracious manner: "When the student

surpasses the master, it simply shows that he had a great teacher."

Thus, it was not until Joe Weider ar-rived on the bodybuilding scene that the sport truly came into the contemporary world. For with the perceptive

eye of an expert coach, Weider was able to see which of the existing techniques worked best and devise new techniques where they were needed. Then,

unlike most of the earlier teachers, he had the foresight to publish those instructions for all to read and use.

Just imagine how different the sport of bodybuilding would be without the many Weiderisms we all take for granted now. A whole new language grew up

around muscle building: supersets, splits, progressive resistance, and a host of other terms are now, thanks to Weider, in the active vocabularies

of every serious bodybuilder.

Obviously, strongmen have come a long way from the age of mystery and uncertainty at the century's turn, to the age of enlightened experimentation

that we enjoy today. Every now and then it's important to look back, if for no other reason than to see just how far we have come. To anyone who

has contemplated it, we have clearly come quite a way. When we think about how bodybuilding has progressed in the last century, it gives one pause

to imagine how far we might go in the next.